By Chase Kahn

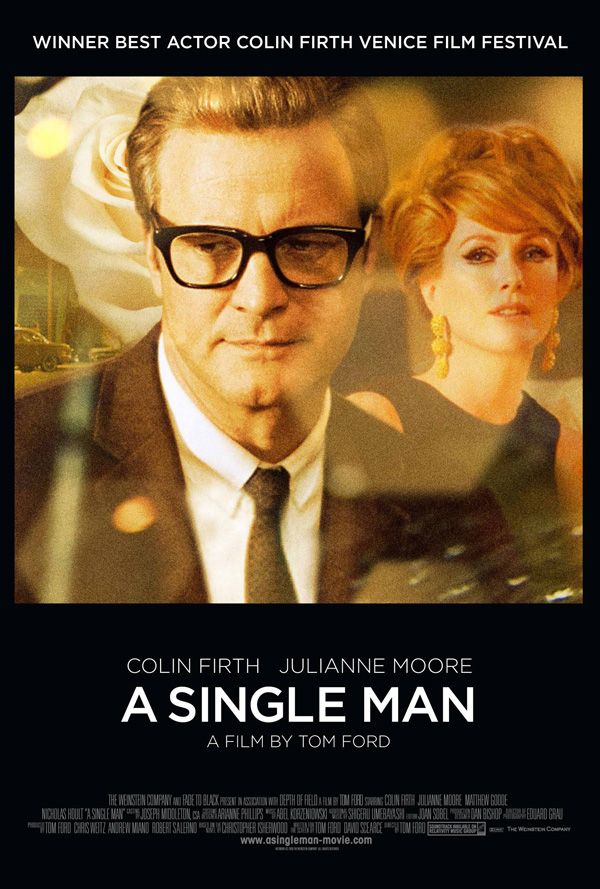

By Chase KahnWhen Colin Firth, the unmistakable star of Tom Ford's striking debut film, is approached for conversation in "A Single Man," he dips into an inquisitive trance - studying the eyes and lips of his conversational opponent as if he were a sculptor - perhaps trying to gain a new perspective on how others see him or how others see the world he inhabits.

It's a world, at least through the eyes of the middle-aged English professor George (Firth), that is on the brink of collapse, a world controlled by fear. It's 1962, the Soviets hold the key to Armageddon, the cultural and sexual minorities are beginning to clash with conservative ideals, and George's longtime lover, a tall, young, frequently shirtless Matthew Goode, has been killed in a car crash.

It's enough to send even the most grounded man into an existential funk of melancholy and misanthropy, but George, one of the 'invisible minorities' that he openly discusses during an Aldous Huxley lecture, is about to embark on a 24-hour journey as lonely as it is life-affirming.

And such is the center of fashion designer Tom Ford's meditation on grief and isolation, which examines a subject in a society which doesn't enable him to grieve outwardly, yet does it in a way that's so sophisticated and elegant that it transcends tragedy into something strangely beautiful.

Cinematographer Eduard Grau's otherworldly 60's Southern California compositions, combined with the production designs and art direction of Dan Bishop and Ian Phillips, (at home in 1962, as architects of AMC's "Mad Men") together with Ford's keen sensual eye and extravagant, albeit occasionally indulgent images, create the most deliciously indelible kind of digital-free visual palette on screens this year.

And Mr. Colin Firth, a slam-dunk Best Actor nominee-to-be, gives a refreshingly subdued and refined performance, free of Oscar clips or audience pandering. He makes George (and therefore the material) universally relatable without ever seemingly trying. And to the audience goes the benefit - for the film becomes something that anyone can connect with and appreciate.

In the end, the title, "A Single Man," becomes something more than a relationship status, it comes to suggest an undesirable state of solidarity and detachment. The beauty in George's personal imprisonment lies in the film's (and life's) unexpected reprieves.

No comments:

Post a Comment